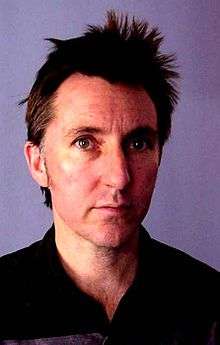

Warrick Sony

| Warrick Sony | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Warrick Swinney |

| Also known as | Kalahari Surfer, Wreck Sony |

| Born |

12 September 1958 Port Elizabeth |

| Origin | South Africa |

| Genres | Electronic, agitprop, world music |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, record producer, composer |

| Instruments | Studio, guitar, drums, bass guitar, tabla, sitar, trombone |

| Years active | 1982–present |

| Labels | Shifty Records, African Dope, Recommended Records, Microdot |

| Associated acts | Kalahari Surfers |

| Website | http://www.kalaharisurfers.co.za |

Warrick Sony is a South African composer, producer, musician and sound designer. He was born Warrick Swinney in Port Elizabeth, in 1958.

He is the founder and sole permanent member of the Kalahari Surfers. They made politically radical satirical music in 1980s South Africa, and released it through the London-based Recommended Records. During this time the Surfers toured Europe with English session musicians.

Sony has produced albums, and ran the Shifty Music label at BMG (Africa) for two years in the mid-1990s. He has also worked as a journalist.

Now based in Cape Town at Milestone Studios, Sony has released more Kalahari Surfers albums, and been involved in art, music and DJ events in the city. He currently works on commercials, film scores and music for theatre.

Early life

Sony was born Warrick Swinney in Port Elizabeth on 12 September 1958.[1] He grew up in the Cowies Hill area of Durban, attending Westville High School where he played in school-based groups doing covers of songs by Jimi Hendrix and The Who.[2] He was influenced by Indian culture, music and cuisine and by the work of Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart.[3] He learned to play tabla at the Hindu Sarat school in Durban.[4] In 1976 he was conscripted into the South African Defence Force, where he declared himself a Hindu pacifist, and was assigned to medical duties and then to band work.[2] During his military service, Sony played B♭ horn, euphonium and drums.[5] He changed his surname from Swinney to Sony to make it harder for the army to get in touch with him for camps; he chose Sony because he liked their products.[6] Whilst in the army he discovered punk rock by coming into possession of the first albums of the Sex Pistols , the Clash and also late 70's reggae . This was to change his musical direction.[5]

Kalahari Surfers

The Kalahari Surfers are a "fictional group" which have served as a long-standing stage name for Warrick Sony's music.[7] He is the only permanent member of the band, and brings in other musicians as and when needed. He adopted the name partly to protect himself from the authorities.[5] The Surfers' music was the first radical white anti-apartheid pop in South Africa,[8] and began with a 1982 home-recorded cassette titled "Gross National Products". Sony distributed it himself;[9] the South African Sunday Times described it as a "daring home-mixed collection of subliminal jive rhythms, sad-sweet jazz sounds, tabla burps, church bells, bird shrieks, political speeches and... other... found sounds",[10] and chose it as one of their three "Terrific Tapes of 1983".[11] The second release was a double single package, "Burning Tractors Keep Us Warm", released by Pure Freude Records. German group Can were involved with this label.[12]

Warrick Sony worked as a freelance sound engineer in the South African film industry, and used this to acquire many of the sound samples he later used in his music.[13] Shifty Records tried to release the 1984 album Own Affairs, but could not find a vinyl plant which would press it.[14] Chris Cutler's London-based Recommended Records pressed the album, the start of a long-standing alliance. Own Affairs was hailed as breathtaking, innovative and humorous by the Weekly Mail.[15] The Sunday Times called it "a music born from the spilled seed of our national sickness and nurtured to nightmarehood in the moral drought of daily life/politics".[16] Cutler helped set up tours, and in 1985 a second album, Living in the Heart of the Beast, was released.[17] Jon Savage wrote in the New Statesman that it was a "success", praised its "viciously critical (and historically intelligent) lyrics", and compared it with early Zappa.[18] The NME called it "brave".[19] The third album, Sleep Armed (1987), has been called "the best snapshot we have of South Africa at the time, right down to the jacket photo of a strange unlikely surfer taken from a 70's movies still. The idea presented the Surfer as an alien in a strange land ..this particular surfer looks like he's from Johannesburg and has never ridden a borad in his life. Hence a more complex view of the white tribes of South Africa".[3]

In 1986, with a live band comprising Mick Hobbs on bass, Alig (from Family Fodder) on keyboards, Tim Hodgkinson (keyboards, sax and slide guitar), and Chris Cutler on drums,[2] Sony performed in the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, the Festival des Politischen Liedes in East Berlin, and London. In 1989 they were the first South African band invited to play in the Soviet Union, where they played Moscow, Leningrad, and Riga.[20]

In 1989 the South African authorities banned the fourth album Bigger Than Jesus,[21] due to concerns about the song "Gutted With The Glory"'s use of the Lord's Prayer, which they deemed "abhorrent and hurtful". A shopper, Mevrou Mulder of Cape Town, was so offended by seeing the record on sale that she organised a petition to the Directorate of Publications. She complained: "The name alone is enough to make any Christian furious, not to mention the words. We as reborn Christians object to the publication of this record and also the distribution of it."[22] Sony successfully appealed, and the record was unbanned on condition that the name was changed to Beachbomb.[23][24] Personality magazine said the album "alternates between sheer poetic brilliance and intellectual nonsense."[25] The first three albums remained banned in South Africa.[26]

Sony worked as a sound recordist covering the release from prison of Nelson Mandela in February 1990, at first for CBS and ABC then later for British television. He has used some of the recordings he made in his musical work.[7] He worked on a documaentary about Donald Woods "Return of the Native where Donald took the crew around South African interviewing various people who had influenced South Africa at large and Woods and Steve Biko as well .[13] Sony worked with Lloyd Ross at a new version of Shifty Records which had been bought by BMG from 1992 onwards concentrating, mostly , on developing and promoting foreign African music in South Africa. He was instrumental in the move to the use of 16-track recording[27] and became a partner in the company when Ivan Kadey emigrated.[28]

|

"Don't Dance", from Own Affairs, 1984

A sample from near the start of the Kalahari Surfers' much-anthologised "Don't Dance", 1984 "9866" from Akasic Record, 2001

|

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

In 1997 Sony left Johannesburg, where he had lived since 1983, after being shot in a hijacking.[29] In 1998 he said he had been against the cultural boycott of South Africa in the apartheid era, as it had prevented important ideas from coming to the country.[30]

Since the turn of the millennium Sony has released a number of Kalahari Surfers albums. Akasic Record[31] (2001) is "a highly sophisticated foray into African-flavoured dubfunk";[32] Muti Media (2003) features a sculpture by Brett Murray on the cover, and Zukile Malahlana from Marekta appears on the album.[33] Conspiracy of Silence (2005) and Panga Management (2007) followed. One Party State (2010) was released on Microdot and debuted at the African Soul Rebels Tour in the UK alongside Oumou Sangaré & Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou.[34] It features Sowetan poet Lesego Rampolokeng on four tracks.[35] The Mail & Guardian called it "a politically drenched album... track for track the most solid South African release of 2010".[36] The Kalahari Surfers performed at the Cape Town Electronic Music Festival in early 2012,[37] and released a live album of the performance.[38] Agitprop was released later in 2012, on Sjambok Music; it was first played at the Unyazi Festival in Durban in September.[39] Agitprop explores Sony's fears about South Africa in the 2010s becoming a one party state under the African National Congress, and includes a song about chemical warfare scientist Wouter Basson.[40] South African Rolling Stone compared it to the KLF, Sly and Robbie and Pink Floyd, and described its "slow evolution of nuance" towards the "desolately upbeat" "Hostile Takeover".[41] Sony says the album was mostly written on the train while commuting to work; he calls the genre "Voktronic, ... a blend of folktronic, and volkspiele with a dose of electronic experimental dubstoep and experimental rolled up into one fat two blade stereo hit."[4] The Kalahari Surfers accepted an invitation in 2010 to tour with "African Soul Rebels " alongside Oumou Sangaré & Orchestre Poly-Rythmo De Cotonou . These were 12 concerts in 12 cities throughout the UK. They playing mostly material from “Agit Prop” which had its South African debut at the Unyazi Electronic Music Festival in Durban in 2012 .

Trans-Sky, remix and production work

Under the name Trans-Sky, Sony produced Killing Time (CD) and Heaven To Touch (EP) with Brendan Jury, and toured South Africa opening for Massive Attack in 1998.[42] He made the album End Beginnings with Lesego Rampolokeng in 1993,[43] which led to a series of concerts in Brazil.[44] In 1998 he worked on Turntabla, an electro-dub project with ex-Orb members Greg Hunter and Kris Weston,[45] and did the sound engineering for a workshop with Brian Eno in Cape Town.[46]

Sony's remix projects include work for M.E.L.T. 2000 on the Busi Mhlongo remix album.[47] He was invited to present a performance for Unyazi: International Electronic Music Symposium at Wits University, Johannesburg in 2005,[48] and co-produced and arranged the album The Triptic (2007) for Polish metal band Sweet Noise.[49]

He designed Kalahari Surfers drum modules for PureMagnetik for Ableton Live music software.[50] He uses a Roland GR09 guitar to trigger his synthesiser, keyboards and samples, and uses Ableton Live and Launchpad with Korg controllers to make his music.[51]

Film, Fine Art, Theatre and TV

As a sound designer Sony worked on the feature film The Mangler, directed by Tobe Hooper.[52] He co-composed (with Murray Anderson) the score for Canadian Broadcasting documentary Madiba: The Life and Times of Nelson Mandela (1996), for which he was awarded the Gemini Award for best music.[53] He composed music for Gerrie & Louise (1997), sound design for Izulu lami (2008) and sound for Zimbabwe (directed by Darryl Roodt, 2008)[54][55] In 2010 he wrote music for Jozi, a comedy directed by Craig Fremont produced by Thom Pictures and Anant Singh.[56] Recent work on Akin Omotoso's " A Hotel Called Memory" is still in the throes of nascence.

Warrick composed an audio piece for : 'Bringing Up Baby: Artists Survey the Reproductive Body', group show at the Castle Cape Town curated by Terry Kurgan in 1998. He also composed an audio piece with Malcolm Payne for Fault Lines project— Inquiries into Truth and Reconciliation a group show in 1998

He worked with artist Rodney Place on his solo show Couch Dancing exhibition.[57] He did music for Ochre and Water: Himba chronicles from the land of Kaoko for Doxa Productions.[58] He worked with Murray Anderson to make music for the Museum of Rock Art[59] and in March 2007, for Turbulence, the South African art exhibition in Red Bull's Hangar 7 event in Salzburg.[60]

He has been involved in multimedia theatre productions doing music and sound design for William Kentridge's Ubu and the Truth Commission (with Brendan Jury)[61][62] and Faustus in Africa,[63] as well as Handspring Puppet's Tall Horse.[64]

Television credits include Apartheid's Last Stand (1999) and Parklife: Africa Discovery Channel (2001).[55] He did music for Ochre and Water: Himba chronicles from the land of Kaoko for Doxa Productions.[58] He works with Murray Anderson doing commercials, film scores and music for theatre.[65] He is based at Milestone Studios, Cape Town, and his advertising work has included commissions from Nissan, Daewoo, Land Rover, and BMW.[44]

Sony had two video works chosen for exhibition at the "Ngezinyawo – Migrant Journeys " Exhibition curated by Fiona Rankin-Smith at Wits Art Museum - these were then chosen for exhibition at the 56th Venice Biennale at the South African Pavilion.[66]

Discography

Kalahari Surfers

- Gross National Products cassette (1982)

- Burning Tractors Keep Us Warm double-single (1983, Pure Freude-Germany)

- Own Affairs (1984, Recommended)

- Living in the Heart of the Beast (1985, Recommended)

- Sleep Armed (1987, Recommended)

- Bigger Than Jesus (Beachbomb in SA) (1989, Recommended/Shifty)

- End Beginnings (with Lesego Rampolokeng) (1989, Recommended/Shifty)

- Paralyzer Ghetto Muffin (1999, Milestone)

- Akasic Record (2001, African Dope)

- Muti Media (2003, African Dope)

- Tall Horse (2005, Milestone)

- Conspiracy of Silence (2005, Microdot)

- Panga Management (2007, Microdot)

- One Party State (2010, Microdot)

- Agitprop (2012, Sjambokmusic.com)

- Tropical Barbie Hawaiian Surf Set — Retro Active Material From 1982-1989 (Compilation) (2014, Roastin’ Records)

- Unoriginal Inhabitants (2015, Sjambokmusic.com)

- Spinning Jenny (May 2015, Sjambokmusic.com)

Compilations

- Munen Muso 1 (Network 77)

- The Sound of Dub (Echo Beach)

- Breathe Sunshine (Amabala)

- The Mothers Township Sessions (Mr Bongo Recordings)

- Yehlisan'umoya Ma-Afrika—Urban Zulu Remixes (2000, M.E.L.T.)

- African Meltdown Volume One - with Greg Hunter

- The Rough Guide to the Music Of South Africa- Rough Guides

- Mandela: Son of Africa, Father of a Nation (Island Records OST1997)

- U KNOW ? Mixes Vol. 1 (2000, M.E.L.T.)

- U KNOW ? Mixes Vol. 3 (2000, M.E.L.T.)

- U KNOW ? Mixes Vol. 4 (2000, M.E.L.T.)

- A Naartjie in our Sosaatie (Shifty)

- New Africa Rock (Shifty)

- Forces Favourites (Shifty)

- Rē Records Quarterly Vol.1 No.1 (1985, Recommended)

- RēR Quarterly Vol.4 No.1 (1994, Recommended)

References

- ↑ Clarke, Donald (1990). The Penguin encyclopedia of popular music. Penguin Books. p. 638. ISBN 0140511474.

Kalahari Surfers: A studio group playing music of Warrick Swinney (b 12 Sep. '58, Port Elizabeth, South Africa), who began at U. of Cape Town, continued in Durban;

- 1 2 3 Maytham, Ellis (December 2007). "Perfect Sound Forever: Kalahari Surfers". Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- 1 2 Jones, Andrew (1995). Plunderphonics, `Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 233. ISBN 0946719152.

- 1 2 Bell, Suzy. "Get Voktronic!! - I really love Africa". Tumblr. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 "African Soul Rebels 2010". Mondomix. 1 December 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Kombuis, Koos. "Warrick Sony Says Juju is Just 'A Blip on the Radar' on a Global Scale". Rolling Stone (South Africa). Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- 1 2 "ArtThrob news". August 2004. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Surf's Up". Melody Maker (5 September 1987).

The Kalahari Surfers are the first radical white African pop.

- ↑ Marie Korpe, ed. (2004). Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today. Zed Books. pp. 89–91. ISBN 1842775057.

Warrick Sony (1991), who worked with Shifty, bypassed the major pressing plants by releasing his first album on cassettes, produced at home and distributed personally.

- ↑ Silber, Gus (7 August 1983). Sunday Times. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Silber, Gus (18 December 1983). Sunday Times. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Molon, Dominic; Diedrichsen, Diedrich (2007). Sympathy for the Devil: Art and Rock and Roll Since 1967. Yale University Press. p. 137. ISBN 0300134266.

- 1 2 Jones, Andrew (1995). Plunderphonics, `Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 234. ISBN 0946719152.

- ↑ Jones, Andrew (1995). Plunderphonics, `Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 235. ISBN 0946719152.

- ↑ Wrench, Nigel (21 June 1985). "Doing the Gunston gig on a sand dune". Weekly Mail.

- ↑ Silbert, Gus (16 June 1985). "Kalahari Surfers". Sunday Times: 41.

- ↑ The album title was taken from the title of a Tim Hodgkinson composition, "Living in the Heart of the Beast" on the Henry Cow album In Praise of Learning

- ↑ Savage, Jon. "Living In The Heart Of The Beast". New Statesman (6 August 1986).

...it works because it is a formal success: cut-up Botha speeches and Afrikaans-speak are set against hi-life and reggae rhythms, while viciously critical (and historically intelligent) lyrics are sung dispassionately over settings that recall early Zappa.

- ↑ Fadele, Dele (3 October 1986). New Musical Express.

Kalahari Surfers bravely ignore the many paradoxes... throw in the gauntlet and preach succession

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Vinassa, Andrea. "SA rocker visits Russia". Star (19 May 1989).

- ↑ The title is a reference to John Lennon's 1966 statement about the Beatles

- ↑ Drewett, Michael (27 February 2012). "Freemuse: South Africa in 1989: CD album banned for offending Christians". Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Jones, Andrew (1995). Plunderphonics, `Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd. p. 232. ISBN 0946719152.

- ↑ De Waal, Shaun. "You cannot judge an album by its cover". Weekly Mail (1-7 December 1989).

- ↑ Nel, Michelle (4 June 1990). Personality. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Legends of Music: The Kalahari Surfers". Muse Online. 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Horn, David; Laing, Dave; Oliver, Paul; Wicke, Peter. John Shepherd, ed. Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World Part 1 Media, Industry, Society. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 669. ISBN 0826463215.

Warrick Sony joined up with Lloyd Ross and formed an association that has continued to exist... Warrick Sony brought with him one of the first Fostex B16 tape recorders and the studio became 16 track.

- ↑ Hopkins, Pat; Kombuis, Koos; Ross, Lloyd (2006). Voëlvry: The Movement that Rocked South Africa. Zebra. p. 87. ISBN 1770071202.

- ↑ "Developing Joburg Future Shacks". Mahala. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Drewett, Michael (2006). Michael Drewett, Martin Cloonan, ed. Popular Music Censorship in Africa. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 33. ISBN 0754681653.

I didn't really support the whole idea of a cultural boycott... I supported the sports boycott because I think that hurt, but ... I think of how much I've learnt from listening to records. For people like Billy Bragg not to have had their records available in South Africa is ridiculous. It is. He's not a huge seller but his ideas needed to come here.

- ↑ Akashic records are part of a mystical state said to immediately follow accidental death.

- ↑ Forrest, Drew. "Mzansi's groove". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kalahari Surfers - Muti Media - African Dope Records E-store". African Dope. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Gedye, Lloyd (7 May 2010). "Dread, beat and blood". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kalahari Surfers One Party State". Mahala. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Gedye, Lloyd (21 December 2010). "10 South African songs that rocked my world in 2010". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "RA News: South Africa". Resident Advisor. 22 February 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kalahari Surfers Live at CTEMF". Kalaharisurfer.bandcamp.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Unyazi 2012". NewMusicSA. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ "Warrick Sony: Surfing the zeitgeist". Mail & Guardian. 25 May 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Young, Roger (August 2012). Rolling Stone (South Africa). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "London Calling". Rhumbelow Theatre. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Jones, Andrew (1995). Plunderphonics, `Pataphysics & Pop Mechanics: An Introduction to Musique Actuelle. SAF Publishing Ltd. pp. 237–238. ISBN 0946719152.

- 1 2 "Milestone Studios: Warrick Sony biography". Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kalahari Surfers & Greg Hunter - Turntabla". Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "ArtThrob". October 2000. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Busi Mhlongo - Yehlisan' umoya Azania (in the mix)". MELT Music. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Project MUSE - Special Section Introduction: UNYAZI". Leonardo Music Journal. 2006. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Sweet Noise - Home Page". Fame Music. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Selector". Puremagnetik.com. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Kalahari Surfers, rabbit-holes and the CTEMF". BPM Life. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ "Acidlogic". Acidlogic. 27 October 2000. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Life and Times (1996) - Awards". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Warrick Sony Filmography". Fandango. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- 1 2 "New York Times: Warrick Sony Filmography". Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Jozi". Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "ArtThrob". ArtThrob. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- 1 2 "DOXA". DOXA. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Rock Art". Rockart.wits.ac.za. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Kalahari Surfers and Friends for Red Bull, Peak People blog

- ↑ "William Kentridge- Interview- Johannesburg, South Africa". February 1998. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Artslink.co.za - Under my Skin". Artslink.co.za. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ Sleeve notes, Muti Media by the Kalahari Surfers

- ↑ Hutchison, Yvette. "The "Dark Continent" Goes North: An Exploration of Intercultural Theatre Practice through Handspring and Sogolon Puppet Companies' Production of Tall Horse" (PDF). Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ↑ "Milestones that matter". 22 March 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Sony at the South African Pavilion". Retrieved 12 May 2015.