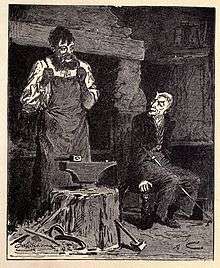

The Smith and the Devil

The Smith and the Devil is a European fairy tale. The story is of a smith who makes a pact with a malevolent being—commonly the Devil (in later times), Death or a genie—selling his soul for some power, then tricks the devil out of his prize. In one version, the smith gains the power to weld any materials, then uses this power to stick the devil to an immovable object, allowing the smith to renege on the bargain.[1]

The tale was collected by the Brothers Grimm in their Children's and Household Tales (published in two volumes in 1812 and 1815),[2] although they removed it in editions of 1822 and later, substituting "Brother Lustig" and relegating references to it to the notes for "Gambling Hansel", a very similar tale.[3] Edith Hodgetts' 1891 book Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tsar collects a Russian version,[4] while Ruth Manning-Sanders included a Gascon version as "The Blacksmith and the Devil" in her 1970 book A Book of Devils and Demons.. Richard Chase presents a version from the Southern Appalachians, called "Wicked John and the Devil."[5]

According to George Monbiot, the blacksmith is a motif of folklore throughout (and beyond) Europe associated with malevolence (the medieval vision of Hell may draw upon the image the smith at his forge), and several variant tales tell of smiths entering into a pact with the devil to obtain fire and the means of smelting metal.[6]

According to research applying phylogenetic techniques to linguistics by folklorist Sara Graça da Silva and anthropologist Jamie Tehrani,[7] "The Smith and the Devil" may be one of the oldest European folk tales, with the basic plot stable throughout the Indo-European speaking world from India to Scandinavia, possibly being first told in Indo-European 6,000 years ago in the Bronze Age.[1][8][9] Folklorist John Lindow, however, notes that a word for "smith" may not have existed in Indo-European, and if so the tale may not be that old.[9]

See also

- Wayland the Smith, a European myth also involving a smith

- Faust, a Germanic legend also involving a pact with the devil

References

- 1 2 "Fairy tale origins thousands of years old, researchers say". BBC. January 20, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Andrea Dezsö, illustrator. Princeton University Press. 2014 [1812]. p. 248. ISBN 978-0691160597. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Schmiesing, Ann (2014). Disability, Deformity, and Disease in the Grimms' Fairy Tales. Wayne State University. p. 69. ISBN 978-0814338414. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Hodgetts, Edith M. S., ed. (2013) [1891]. Tales and Legends from the Land of the Tzar: Collection of Russian Stories. Nabu Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1294147350. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Chase, Richard (1948). Grandfather Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ George Monbiot (January 1, 1994). "The Smith and the Devil". George Monbiot website. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ↑ Graça da Silva, Sara; Tehrani, Jamshid J. (January 20, 2016). "Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales". Royal Society Open Science. The Royal Society. doi:10.1098/rsos.150645. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Fairytales much older than previously thought, say researchers". The Guardian. January 20, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- 1 2 Chris Samoray (January 19, 2016). "No fairy tale: Origins of some famous stories go back thousands of years". Science News. Society for Science & The Public. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

External links

- Text of the tale by Brothers Grimm (German)