LGBT writers in the Dutch-language area

LGBT writers in the Dutch-language area are writers from de Lage Landen, that is Flanders and the Netherlands,

- who were homosexual

- wrote for a homosexual audience

- wrote about homosexuality

According to Gerrit Komrij qualifying for at least two of the above makes someone a gay author.[1]

The first of these authors owed much to the late 19th century decadent literature, with names like Georges Eekhoud in Belgium and Jacob Israël de Haan in the Netherlands. After the second world war Gerard Reve, and later Gerrit Komrij and Tom Lanoye became the leading names.

Most of these LGBT writers are Dutch-language writers contributing to Dutch-language literature, some of them acquiring a place in the Canon of Dutch Literature.

Before late 19th century

Before the last decades of the 19th century words like uranism, homosexual, sapphism, lesbian and transvestite didn't exist. Being called a true Sappho of Lesbos was a high compliment for female poets, without sexual connotations.[2] Words like sodomy, pederast and hermaphrodite existed and had their Dutch-language counterpart, but only very partially covered what would become LGBT (Dutch equivalent: holebi) in a more modern understanding.[3] Generally the older terms, most of all sodomy, had a negative connotation. Writing about these topics was usually either pornographic or in terms of condemnable (religious) sin. From the 19th century these subjects were also more often treated in medical science, which led to the more modern terminology.

Authors writing in a positive manner about bonds between people of the same sex spoke about friendship (in Dutch: vriendschap). Such friendships could be qualified as romantic friendships. Whether there was a component of sexuality was unclear and if so, not outspoken. Friendship was certainly not always a euphemism for something more, nor even for Platonic love.

A friendship was recorded between the writers Betje Wolff and Aagje Deken: they also wrote about the topic of true friendship. Johannes Kneppelhout, choosing Klikspaan (= snitch) as pen name for some of his writings, was a 19th-century example of writing about friendship in this sense, for example in his 1875 Een beroemde knaap (A Famous Boy).

Also Guido Gezelle doesn't really qualify as a LGBT writer in Komrij's definition: as a catholic priest he certainly didn't write explicitly for a gay audience, nor was any of his writing strictly speaking about homosexuality. Nonetheless Dien avond en die rooze (That Evening and that Rose) is generally understood to have been a love-poem for Eugène van Oye, one of his students he had befriended.

Fin de siècle

Late 19th century Dutch writers that tried to get LGBT literature across the border of pornography include Louis Couperus.[4] Georges Eekhoud published Escal-Vigor in 1899. In the early 20th century Jacob Israël de Haan started publishing his LGBT-themed works. They had Oscar Wilde and Joris-Karl Huysmans as contemporary examples outside the Dutch-language area, and Magnus Hirschfeld for the non-fiction.

Tachtigers

For Louis Couperus' generation of Dutch-language authors, known as the Tachtigers, writing openly about homosexuals in novels was impossible, while writing about antiquity left more layway.[5][6] In 1891 Couperus published his novel Noodlot with an 'effeminate' protagonist, while his more explicit novel De berg van licht (1904–05) employed the technique of placing the action in ancient Rome.[6] It was generally known that Couperus was homosexual.[7]

Arnold Aletrino was a LGBT Tachtiger writing both fiction and non-fiction.

Other Tachtigers with same-sex tendencies, like Willem Kloos, writing passionate poems about men, and Lodewijk van Deyssel, describing a special friendship with one of his fellow students in his 1889 De kleine republiek, repressed their feelings.[8] Albert Verwey's cycle of 44 sonnets, Van de liefde die vriendschap heet (On Love that is Named Friendship), written in response to Kloos' passion for him, was perceived as coded homoeroticism, although mostly about spiritual love in intent.[8]

Georges Eekhoud

Georges Eekhoud was a Flemish author writing in French. In 1899 his LGBT themed novel Escal-Vigor was published. It led to a trial in 1900, which Eekhoud won.[9]

Hélène van Zuylen

After marriage Hélène van Zuylen, by birth a French Rothschild, came to live in a castle near Utrecht. Together with her English lover Renée Vivien she published poems and novels in French, among others in 1904 L'Être double, a novel on Androgyny (under the pseudonym Paule Riversdale).

Jacob Israël de Haan

Jacob Israël de Haan describes living in the Netherlands as a nightmare that continues after waking up,[9] and looked for Eekhoud as an ally to escape from this narrowminded society[10] when dedicating his "rape of Jesus" short story to him.[9] The two authors kept in contact by letter.[9][11]

For his style, De Haan was indebted to Couperus. De Haan's style oscillates between the l'art pour l'art style of the Tachtigers and a more engaged, less embellished style.[9] His Tachtigers friends had given him however little support when getting in trouble after the publication of his first explicit gay novel Pijpelijntjes in 1904.[9] In the first edition of the book de Haan's friend Arnold Aletrino had been portrayed too recognisable.

Light reading

Under a cloak of moralizing against fornication some authors went in great detail describing libidinous topics. Also for homosexuality this genre was practiced, for instance Feenstra Kuiper's 1905 illustrated pornographic novel Jeugdige zondaars te Constantinopel (Youthful Sinners in Constantinople), reading as a gay tour guide to the city.[8]

Easy-reading novels, usually with a melodramitic plot, were provided by M. J. J. Exler (Levensleed, 1911), Marie Metz-Koning, and Maurits Wagenvoort (Het koffiehuis met de roode buisjes, 1916).[12]

A play about Oscar Wilde was written by Adolphe Engers in 1917.[12]

Non-fiction

In 1883 N. B. Donkersloot, editor of a medical journal, was the first to publish a testimony originally written in Dutch of a man preferring same-sex.[13] Around this time most Dutch-language medical literature on the subject was however borrowed from foreign examples, mostly from Germany and France.[14]

From 1897 to 1908 Arnold Aletrino published his non-fiction works about uranism, in which he described chaste friendship as a superior form of uranism.[15] Lucien von Römer, who had written love poetry for a man when he was young, published in Hirschfeld's journal in the early 20th century. He was also the first to conduct an inquiry on sexual behavior, and defended the sexual act for homosexuals. His major work was Het uranisch gezin (The Uranian Family, 1905).[16]

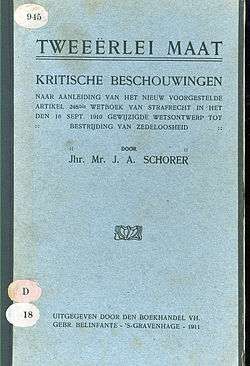

In 1911 a new article in Dutch law (248bis) discriminated against homosexuality. Jacob Schorer, a lawyer, started publishing against this law.[17] Aletrino and Römer supported, but no longer published on the subject. Also before the first World War Hubertus J. Schouten had published on similar topics, under various pen-names.[18]

Interbellum

Lesbian Maria Nys, later Mrs. Aldous Huxley, left Belgium before moving into literary circles like the Bloomsbury Group. Her contributions to literature are limited, the best known of these is her tampering with the text of Lady Chatterley's Lover, which led its author D. H. Lawrence to be discontent over the first print of that work.[19]

During his Berlin period (1918—21) Belgian avant-garde poet Paul van Ostaijen wrote homoerotic letters, and would have experimented with gay sex.[20]

In 1919 poet Pieter Cornelis Boutens was hiding behind a fictional name when he published his homoerotic Strophen uit de nalatenschap van Andries de Hoghe. In 1930 he was refused a knighthood for rumours of his homosexuality.[7] Other poets in the Netherlands included Willem de Mérode, pen name for W. E. Keuning (Ganymedes, illustrated by Johan Dijkstra, 1924) and Willem Arondeus (his homoerotic poems Afzijdige Strofen were however only published many years after his death).[21][22]

New melodramatic novels, similar in plot to those that were published before the end of the war, were published by J. H. François, writing under the pen name Charlie van Heezen (Anders, 1918 and Het masker, 1922), Johan de Meester (Walmende lampen, 1920), Bernard Brondgeest (Doolhof, 1921), Wilma (God's gevangene, 1923), and Adolphe Engers together with Ernst Winar (Peccavi...??? Roman uit het Haagsche leven, 1920).[12] A gay play Wat niet mag... was written by J. M. IJssel de Schepper-Beckers in 1922.[23]

Avant-garde artist Til Brugman, fluent in several languages, publishes poems from 1923. She also writes literary grotesques, amongst others on sexual minorities, which she belonged to, living together with LGBT lovers like Hannah Höch.

Edith Werkendam lived in the Netherlands and Belgium. Several of her novels are about LGBT topics, among which De goddelijke zonde about bisexuality, published in 1928.[24] Josine Reuling's 1937 novel Terug naar het eiland can be read as a commentary on Radclyffe Hall's 1928 The Well of Loneliness.[25]

Jef Last published two gay novels: Zuiderzee (1934) and Het huis zonder vensters (1935).[23] In 1936 Last and André Gide travelled across the Soviet Union. Both published about this trip, with some attention to LGBT topics, Gide in 1936 and Last in 1966 (Mijn vriend André Gide).[26] Together with Harry Wilde Last published a novel (Kruisgang der jeugd, 1939) about Marinus van der Lubbe, against a trend that equalled homosexuality with nazism.[27] After the war there were Last's De jeugd van Judas (1962) and the pornographic De zeven caramboles (posthumous, 1973).[28]

Decadent poets were attacked by Seerp Anema in his 1926 Moderne Kunst en Ontaarding.[21] Jacob Anton Schorer continued to publicize in defense of homosexuality in the period between the wars. A. J. Luikinga published under the pen name Commutator, among others his 1927 defense Homosexualiteit.[29] In 1929 Ernest Michel published an anti-gay writing Anti-homo: Een geschrift tegen de weekdieren onzer samenleving.[30] Koos Vorrink warned against homosexuality in his 1933 Om de vrije mens der nieuwe gemeenschap: Opvoeding tot het demokratiese socialisme. 1934 publications by J. H. van der Hoop (Homosexualiteit) and Benno J. Stokvis (Homosexualiteit en strafrecht) were equally heteronormative.[31] Stokvis' 1939 De homosexueelen: 35 biographieën gave insight in daily life of LGBT people.[31] Medical publications concentrated on possible cures for homosexuality, like castration (e.g. G. Sanders Het castratievraagstuk, 1935).[32] L. Bender's 1937 Verderfelijke propaganda summarized the Catholic rejection of homosexuality.[33]

A few months before the second world war came to the Netherlands Jaap van Leeuwen (pen name: Arent van Santhorst), Nico Engelschman (pen name: Bob Angelo) and Hann Diekmann became the authors and editors of a new periodical Levensrecht defending LGBT rights.

After the second world war

In 1966 Gerard Reve's Nader tot U was published, containing a description of the author having sex with God in the guise of a young donkey — the press was alarmed.[34] It took to the early 1980s, with a series of short stories by De Haan republished, that the press started to realize that Reve had been less ground-breaking on LGBT themes in the Dutch-language area than assumed.[35]

Reve remained the most influential of Dutch-language LGBT writers after the second world war. In the 21st century LGBT writers became less concerned with their LGBT status, being a good author is their primary concern.[34]

Dutch-language literary events, like poetry nights ("De Nacht van de Poëzie" organized since 1966), and prizes (like AKO Literatuurprijs, Royal Academy of Dutch Language and Literature Prize) often have an international dimension, bringing together writers from the Low Countries.

Non-fiction writings showed a major change towards acceptation of homosexuality in the early 1960s. For instance, the first edition of Tolsma's Homosexualiteit en homoërotiek (1948) warned against homosexuality, and rejected it. The second edition of that book (1963) had replaced that language by words of tolerance.[36]

Gerard Reve and the post-war generation

Gerard Reve's novel De Avonden was published in 1947 and gave a new start for LGBT writing in Dutch, both in the Netherlands and in Flanders (where Reve spent the last years of his life). The significance of Reve and his first novel were tremendous. Within a year after publication De Avonden had received 50 book reports in the press,[37] and by the end of the 1960s it was considered a timeless classic of Dutch literature.[38] The book has often been compared with Salinger's Catcher in the Rye.[39] In the early 21st century Dick Matena made a graphic novel version of De Avonden.[38] For several generations Dutch-language LGBT writers would pay their tribute to Reve.

Further novels by Reve with a homosexual theme include Melancholia (1951), In God we Trust (two chapters published in 1957), Op weg naar het einde (1963), Nader tot U (1966), and Prison Song in Prose (1967).

Hans Warren published his first poems in 1946. Second wave of creativity from the late 1960s. From 1978 he started a relation with the much younger Mario Molegraaf, with whom he co-authored. The 23 volumes of Warrens diary were published from 1981 to 2009.

Jac. van Hattum wrote poetry and short stories (e.g. Mannen en katten, 1947; Un an deplus, un an de moins, 1955; De liefste gast, 1961; De wolfsklauw, 1962; De ketchupcancer, 1965), receiving recognition by Reve.[40] Hans Lodeizen received most recognition after his early death in 1950. His poetry was cryptic on homosexuality.[40] Poet Jan Hanlo fell in love with a Moroccan boy: his reminiscence of this love was published in 1971 as Go to the mosk: Brieven uit Marokko.[41]

Homosexual writers and poets of this first post war generation include Jaap Harten, Bernard Sijtsma, Adriaan Venema, Jos Ruting, Astère-Michel Dhondt and Frits Bernard (a.k.a. Victor Servatius).[28] Annie M.G. Schmidt included gay characters in her texts for the performing arts.[28]

Among the Dutch female writers addressing homosexuality in the post-war generation was Anna Blaman: the erotic passages of her 1948 novel Eenzaam avontuur (Lonely Adventure) stirred contemporary authors to a fake process so-called regarding her literary style.[42] There was also Dola de Jong, whose book The Tree and the Vine was first published in 1951 (after she had moved to America fleeing the Nazis); it is about a lesbian couple during World War II and is likely her best-known work apart from her mystery novels.[43] It was republished in 1996 by the Feminist Press.[44]

.jpg)

In Belgium there was another author from Flanders writing in French: with her 1951 novel Le Rempart des Béguines Françoise Mallet-Joris creates a succès de scandale over its lesbian content.[45] In 1963 Carla Walschap was the first Dutch-language Flemish author with a novel on a lesbian theme (De eskimo en de roos).[45]

Andreas Burnier (pseudonym for Catharina Irma Dessaur): first novel Een tevreden lach (1965) describes how she discovered being a lesbian. She is known to be the first who took lesbianism for granted in the Netherlands, just as Reve had for male homosexuality.

Next generation of Dutch-language LGBT writers

- Gerrit Komrij: poet, novelist, playwright, critic, polemist and translator. Verwoest Arcadië (Destroyed Arcadia, 1980) is an autobiographical novel about discovering boys and books when he was young. Komrij also wrote LGBT-themed essays like Averechts (1980).

- Tom Lanoye: poet, novelist, playwright, scenarist, columnist, essayist. Thesis about Hans Warren's poetry. First novel Kartonnen dozen (Cardboard Boxes, 1991) is about his discovery of homosexual feelings as a young boy. Most famous LGBT writer of his generation in Belgium.

Tom Lanoye in 2013

Tom Lanoye in 2013 - Eric de Kuyper: homosexuality as central theme in his work, which encompasses various forms of writing and film-making. His first film (Casta Diva, 1983) combines images of attractive men with opera arias.

- Maarten 't Hart's novels Stenen voor een ransuil (1971) and Ik had een wapenbroeder (1973) showed a homosexual sensibility, based in the author's transgender feelings.[46]

- Kees Verheul: Kontakt met de vijand (1975) and Een jongen met vier benen (1982).[46]

- Anton Brand publishes gay-themed short stories, travel reports and essays from 1978.

- A. Moonen writes in a minimalist style about his sexual preferences in Openbaar leven (1979) and De anale variant (1983).[46]

Doeschka Meijsing in 2011

Doeschka Meijsing in 2011 - Willem Bijsterbosch, poet publishing from 1981, describes same-sex relationships in his novels.

- Dirkje Kuik (born as William): transgender theme, for instance in Huishoudboekje met rozijnen (1984)

- Rudi van Dantzig Voor een verloren soldaat (1986), film version For a Lost Soldier (1992)

- About SM: Jim Holmes (poetry) en Jaap van Manen (short story)

- Anja Meulenbelt links feminism and the discovery of a lesbian identity in her 1976 novel De schaamte voorbij.

- Elly de Waard: feminist and poet (published from 1981), "uncrowned queen of the lesbians"[47]

- Astrid Roemer, novelist and playwright born in Suriname, treats topics like discrimination and identity, including LGBT identity.

- Gerda Meijerink's 1985 novel De vrouw uit het Holoceen describes the erotic attraction between two women.[24]

- Sjuul Deckwitz: lesbian, ironic neoromantic cult poems[48]

- Frans Kellendonk: Kellendonk's last novel Mystiek lichaam (Mystic Body, 1986) has creation as only meaningful principle as its central theme. Kellendonk regarded homosexuality as a sterile lifestyle.

- Doeschka Meijsing: despite being a lesbian, Meijsing takes a less favourable view on homosexuality. Her last novel Over de liefde (About Love, 2008), about her break up with Xandra Schutte, won the AKO Literatuurprijs.

Writers for LGBT stage productions included Komrij, Gerardjan Rijnders, Cleo van Agt, Han van Delden (pseudonym: Hans van Weel), Cas Enklaar and Joop Admiraal.[49]

Periodicals - comic strips

In the Netherlands Levensrecht continued after its war-time suspension with Van Leeuwen, Engelschman and now Jo van Dijk. The periodical was later renamed to Vriendschap (Friendship) published by COC Nederland. Gerard Reve contributed to another COC periodical Dialoog from 1965 to 1967, provoking a lawsuit over his description of intercourse with God in the guise of a donkey (which he eventually won).[50][51]

In Flanders groups bringing together Flemish LGBT people existed from the early 1960s, the first of which was COC Vlaanderen, closely connected to COC Nederland.[52] Some of these groups had their local bulletins, but they remained exclusively dependent on COC Nederland for the broader publications until 1972.[53]

LGBT periodicals published in the Netherlands targeting an international Dutch-language readership include Expreszo (published from 1988)[54] and Madam (for gay women, publication stopped 1999).[55] From 2013 the Flemish ZiZo-magazine and Gay&Night from the Netherlands collaborated for the publication of Gay&Night-ZiZo targeting a younger audience than ZiZo-magazine.

Tom Bouden, author of comics on LGBT themes, published in most of the LGBT periodicals in Flanders and the Netherlands. His first collection of strips (Flikkerzicht) was published in 1993. Bouden turned Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest into a contemporary all-male graphic novel in 2001.[56] The gay kiss in that comic didn't go unnoticed.[57] The Dutch comic artists Floor de Goede, Ype Driessen and Abe Borst are mostly known for their autobiographical webcomics.

Writing for youngsters on LGBT topics

One of the first to write on LGBT topics for youngsters was Agalev founder Luc Versteylen in his 1981 De Paradijs Ervaring.[59]

LGBT writers usually writing for children and/or teenagers (but not always on LGBT topics) include:

- Koos Meinderts: Man lief en heer loos (1998).[60]

- Bart Moeyaert: Het is de liefde die we niet begrijpen (1999), a novel for the youth, takes homosexuality as a fact for its protagonist, not giving much attention to a process of acceptation.[61]

- Ted van Lieshout, writes for children primarily. In his 1996 short novel Gebr. he writes about his coming out and his younger brother who also was homosexual.[60] In his 2012 book Mijn Meneer he relates about an affair he had with an older man when he was young. His 1999 Een kleine liefde had a similar topic (relationship with a man from the perspective of a boy).[46]

- Actor Mark Tijsmans[58]

Also Dirk Bracke writes for young people, one book with a LGBT theme: Zij en haar (2005)

Genootschap voor Tegennatuurlijke Letteren

in 1983 Johan Polak became ward to the Dutch Genootschap voor Tegennatuurlijke Letteren. Members included in this group:

- Nop Maas: Reve's biographer (3 volumes from 2009)

- Theo van der Meer: historian, doctorate on Sodoms zaad in Nederland. Het ontstaan van homoseksualiteit in de vroegmoderne tijd (Seed of Sodom in the Netherlands: Beginning of Homosexuality in the Early Modern Age), 1995

- Cees van der Pluijm: poetry from 1980s, correspondence with Robert Long

- Paul Snijders: publicist on LGBT related themes, among others on Louis Couperus (from 1980s)

Book-writing celebrities

Fashion designer Max Heymans wrote his autobiography Knal in 1966. In 1984 actor Albert Mol wrote his autobiography "Zo" zijn, which also covered gay life in the Netherlands before the second World War.[62] Singer-songwriter and entertainer Robert Long published his autobiographical novel Wat wil je nou in 1988. Manfred Langer, founder of the gay disco iT in Amsterdam published Alle geheimen van de iT in 1993. Politician Pim Fortuyn was open about his homosexuality. He published books on political topics from 1994.

In Belgium several LGBT people who became known by radio and/or television appearances wrote books: Tom De Cock (horror novel published in 2001),[63] Koen Crucke (books about losing weight which he wrote from his own experience), Felice Damiano (a book about discovering homosexuality in a boarding school published in 2006), Mark Tijsmans (actor writing books for the youth),[58] Jo de Poorter (radio and television host and communication advisor writing books on becoming successful and on lifestyle), Jani Kazaltzis (fashion related books), Frank Dingenen (bundle of short columns, known as cursiefjes in Dutch, published in 2013), Bart Stouten (host on Klara writing poetry and novels).[64][65]

Opera director Gerard Mortier, all in all not so very open about his own homosexuality,[66] wrote books about opera and about culture politics.

Boudewijn Büch complied to at least one of Komrij's criteria: he wrote about LGBT subjects like androgyny.

Youngest generation of novelists and poets

- Maxim Februari (born Marjolein Drenth): first novel De zonen van het uitzicht (1989) has intersexuality as theme. Woman to man transition in 2012-13.

- Renate Stoute (born René), poet and novelist: first novel with trangender theme in 1991. In her 1999 autobiography (Uit een oude jas vol stenen: De geboorte van een vrouw) Stoute describes identifying as a lesbian woman, leading to gender reassignment surgery in 1996.[67]

- Willem Melchior wrote novels with themes as voluptuous death wish and sado-masochism, from 1992 (De roeping van het vlees). He was compared with Couperus[5]

- Han Nefkens writes about HIV and Aids in his 1995 Bloedverwanten.

- Ton Kors De tijd van Anton de Lange (1995) cruising in Amsterdam, fetishes and death by Aids.[60]

- Pim Wiersinga, Gracchanten (1995), set in antiquity.[60]

- Jacob Vredenbregt, among others Intermezzo in de Leeuwenstad (1996) has an LGBT side-theme.

- Bram van Stolk, S-1 (1996) — autobiographic about his time in the German army in 1961.[60]

- Leo Wisselink, De hondenjaren (1996) about homosexuality in a provincial town.[60]

- Anne Golen, Eenzame strijd (1997), problematizing homosexuality from a Christian background.[60]

- Dens Vroege De dictatuur van de begeerte (1998), gay nightlife in Amsterdam.[60]

- Gerard van Emmerik's first novel Misha's koorts (Misha's Fever, 1998) is about a boy meeting an older gay man.

- Erwin Mortier, novelist, poet, columnist and essayist wrote his second novel (My Fellow Skin, 2000) on a gay theme: sudden death interrupting the awakening of gay feelings of a school boy. Mortier came out in his 2003 bundle of essays A Plea for Sinning. His 2007 book Evenings on the Estate: Travelling with Gerard Reve was a tribute to the older author he knew personally.[68]

Ida Gerhardt in 1968

Ida Gerhardt in 1968 - Marjolein Houweling: 2001 novel about a violent lesbian relationship after a divorce: Niemandsland.

- Saskia de Coster published novels from 2002. As a columnist she takes stance on LGBT topics.

- Arthur Japin's second novel De droom van de leeuw (The Dream of the Lion, 2002) is autobiographic about his relation with Frederico Fellini.

Karin Spaink in 2006

Karin Spaink in 2006 - Gerbrand Bakker published highly acclaimed novels from 2002. Open about his homosexuality on his weblog[69]

- Minke Douwesz wrote a lesbian-themed novel in 2003: Strikt.[24]

- Jos Versteegen, poet also known for his contributions to Homo-encyclopedie van Nederland (Gay Encyclopedia of the Netherlands, 2005), co-authored with Thijs Bartels.[70]

- Mario Molegraaf had his first poems published in 2011. He translated poetry of the Greek gay poet Constantine P. Cavafy in Dutch. He had started these translations together with Hans Warren.

Other LGBT novelists of this generation include Flemish Luc Boudens and Paul Mennes, and Koos Prinsloo from South-Africa. Oscar van den Boogaard moved from the Netherlands to Belgium. In the Netherlands, Jaap Harten, Bas Heijne, Gert-Jan van Exel, Th. van Os and Joost van Weel. Obe Postma is a poet writing in Frisian.[60]

Non-profit organisations like Behoud de Begeerte continue the tradition of bringing together authors from the Low Countries in literary events. Participants include Tom Lanoye, Gerrit Komrij, Dimitri Verhulst, Saskia de Coster, Erwin Mortier and Bart Stouten.[71]

Another initiative making little distinction which side of the border between Flanders and the Netherlands writers originated from were the Gay 2000 through Gay 2004 glossy yearbooks (Snoecks style) published from 1999 to 2004.[72]

Others

- Ida Gerhardt, poet and translator of ancient texts, was secretive about her private life, including her lesbian relationship with co-translator Marie van der Zeyde.[73] Gerhardt wrote poems about Sappho (the first of these published in 1945), and translated her poetry.[47] Apart from her own poetry Gerhardt (and Van der Zeyde) are best known for their translation of Biblic Psalms, used as much in Flanders as in the Netherlands, by Catholic and Protestant denominations.[74]

- Gert Hekma is a researcher at the University of Amsterdam who published widely about LGBT-issues and their history in The Netherlands.

- Henri Nouwen, Catholic priest, LGBT status only fully revealed after his death in 2004.

- Xaviera Hollander, best known for her book The Happy Hooker, turned gay in the late 20th century, but eventually married a man in 2007.

- Karin Spaink: activist, also about LGBT rights in her writings.

- Xandra Schutte: editor of De Groene Amsterdammer, published a book of essays in 1999.

- Hanneke van Buuren: Vrouwen die van vrouwen houden - een documentaire, 1977

- Maaike Meijer, Mieke van Kasbergen, Ineke van Mourik and Dorelies Kraakman: Lesbisch Prachtboek, 1979

- John De Witt, Kurt Van Eeghem and Yves Jansen (eds.): Heerlijk: over mannelijke homoseksualiteit, 1982

- Majo Van Ryckeghem, about self-acceptance and coming out in Thuiskomen: Scènes uit een lesbisch bestaan (1992)

- Veronique Renard: intersexual (Klinefelter), wrote about her experience of man to woman transition.

- Judith Schuyf is an archeologist and researcher into LGBT-issues, e.g., her study of the recent history of lesbianism in the Netherlands: Een stilzwijgende samenzwering. Lesbische vrouwen in Nederland 1920-1970 (1994)

- Saskia Wieringa is a researcher who published several non-fiction works about same-sex relations.

References

- ↑ Lekker lezen: homo- en lesboliteratuur - circa 1750 tot nu at www

.homogeschiedenis .nl - ↑ Meijer 1998, Introduction pp. 1-23

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 3

- ↑ "Literatuur en porno" at www

.literatuurgeschiedenis .nl - 1 2 Schoonhoven 2003

- 1 2 Hekma 1990 p. 66

- 1 2 Snijders 2003

- 1 2 3 Hekma 2004, p. 28

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rob Delvigne and Leo Ross. Introduction to De Haan's Nerveuze Vertellingen (1983) p. 8-50

- ↑ De Haan 1983 p. 52

- ↑ Rob Delvigne and Leo Ross. "Ik ben toch zo innig blij dat u mijn vriend bent" in De Revisor Nr. 3 (1982) pp. 61-71

- 1 2 3 Hekma 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 32-33

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 31-35

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 36-37

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 37-39

- ↑ Schorer 1911

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 43-44

- ↑ Stan Lauryssens. Mijn heerlijke nieuwe wereld (2001)

- ↑ Pleij 1996

- 1 2 Hekma 2004, p. 52-53

- ↑ Lutz van Dijk. Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History. Routledge. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0415159830.

- 1 2 Hekma 2004, p. 53

- 1 2 3 Ten Duis 2013

- ↑ Ten Duis 2013, pp. 31-32

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 55-56

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 56

- 1 2 3 Hekma 2004, p. 71

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 55

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 58

- 1 2 Hekma 2004 p. 56

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 48

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 59

- 1 2 Meester 2012

- ↑ Van Eeden 1984

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 68

- ↑ Lamon 2011 p. 6

- 1 2 Lamon 2011 p. 7

- ↑ Joost Zwagerman. "Anker Amerika" in De Volkskrant 25 October 2013 pp. 3-4

- 1 2 Hekma 2004, p. 69

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 70

- ↑ Ten Duis 2013, p. 34

- ↑ "Dola de Jong, 92, Author of Mystery Novels". nytimes.

- ↑ "Author Dola de Jong dead at 92". Napa Valley Register. 23 November 2003.

- 1 2 Ronny De Schepper 2012

- 1 2 3 4 Hekma 2004, p. 99

- 1 2 Meijer 2010, p. 203

- ↑ Meijer 1998, p. 19

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p.98

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p.70

- ↑ Fekkes 1968

- ↑ Hellinck 2002, p. 7

- ↑ Hellinck 2002, p. 14

- ↑ Geurds and De Heide 2013, p. 22

- ↑ Geurds and De Heide 2013, p. 17

- ↑ Tom Bouden at the Prism Comics website

- ↑ Smith 2011

- 1 2 3 As of 2014 Tijsmans no longer described himself as gay, see "Flikken-ster Mark Tijsmans leeft als kluizenaar", Het Nieuwsblad 19 August 2014

- ↑ Werkgroep Liever Leven 1981, for instance "Het Bibber Gesprek" pp. 371-374

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Verstegen 1999

- ↑ Tsjip/Letteren 2004, p. 31

- ↑ Hekma 2004, p. 46, 142

- ↑ John Vervoort. "De openbaring van Tom de Cock" in De Standaard 22 March 2001

- ↑ Bart Stouten wint award voor ‘vergeten roman’ at www

.boekenkrant .com - ↑ Bart Stouten, 'Bidden om verboden vruchten' at Behoud de Begeerte website

- ↑ Lucas Vanclooster. "Requiem voor een operarebel" at deredactie.be (09 March 2014)

- ↑ Jeanne Doomen. "De man die wist dat zij een vrouw was" in De Volkskrant (24 March 2000)

- ↑ Erwin Mortier. "BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION: How to be as immodest as possible" at erwinmortier

.be - ↑ Gerbrand Bakker. Halfblote mannen at www

.gerbrandsdingetje (19 April 2013).nl - ↑ Bartels and Versteegen 2005

- ↑ begeerte

.be - ↑ Hafkamp et al. 1999-2004

- ↑ Kummer 2004, p. 179

- ↑ Van der Pluijm 2010

Bibliography

Dutch-language sources

- "Het taboe doorbroken?: Holebiseksualiteit in de adolescentenroman" in Tsjip/Letteren (jg. 14). ThiemeMeulenhoff (2004). pp. 30–35

- Thijs Bartels and Jos Versteegen (editors). Homo-encyclopedie van Nederland. Uitgever Anthos (August 2005). ISBN 9789041405661

- Ronny De Schepper. “L’homme écrit pour être aimé, la femme pour être libre” (Marina Bianchi) (9 December 2012)

- J. ten Duis. Van ‘tegennatuurlijk’ tot ‘pottentrots’: de receptie van lesbische literatuur in de twintigste eeuw. University of Groningen (2013)

- Ed van Eeden. "De miskende decadent: De Haans Nerveuze Vertellingen maken Gerard Reve minder uniek" newspaper article (21 July 1984)

- Jan Fekkes. De God van je tante. Amsterdam, Arbeiderspers (1968)

- Saskia Geurds and Thomas de Heide Waarom zijn er meer homobladen voor mannen dan voor vrouwen?. Fontys Hogeschool Journalistiek, Tilburg (27 mei 2013)

- Jacob Israël de Haan. Nerveuze Vertellingen with an introduction by Rob Delvigne and Leo Ross. Bert Bakker (1983)

- Hans Hafkamp, Jos Versteegen, Lex Spaans and René Abbühl (eds.) Gay 2000: cultureel jaarboek voor mannen. Vassallucci (1999). From the same series:

- Gay 2001 (2000)

- Gay 2002 (2001)

- Gay 2003 (2002)

- Gay 2004 (2004)

- Gert Hekma. "Nederland: Couperus en De Haan" in Grensgeschillen in de seks: bijdragen tot een culturele geschiedenis van de seksualiteit (1990) pp. 66–68

- Gert Hekma. Homoseksualiteit in Nederland van 1730 tot de moderne tijd. narcis.nl (1 January 2004)

- Bart Hellinck. een halve eeuw (in) beweging: een kroniek van de vlaamse holebibeweging. federatie werkgroepen homoseksualiteit (FWH), Ghent. (December 2002)

- Jeroen Kummer. "Wanneer schrijf jij eens wat over jezelf?: De correspondentie van Ida Gerhardt met Catharina Ypes" (2004)

- Lien Lamon. Gerard Reves De avonden van roman naar beeldroman: Narratieve aspecten van Dick Matena's adaptatie Ghent University (2011)

- Madelon Meester. "Voorvechters gezocht" in De Volkskrant (1 August 2012)

- Maaike Meijer. "Elly de Waard (1940): Die intiemste spier, het hart" in Schrijvende vrouwen: Een kleine litteratuurgeschiedenis der Lage Landen 1880-2010. Editors: Jacqueline Bel and Thomas Vaessens. Amsterdam University Press (2010) pp. 203–210

- Sander Pleij. "Kunstbroeders" in De Groene Amsterdammer (17 July 1996)

- Cees van der Pluijm. "Namiddaglicht in een uitgestorven pastorie" in De Gelderlander (19 March 2010), p. 17

- Erik Schoonhoven. "Het belang van onvolmaaktheid: Een vraaggesprek met Willem Melchior" at www

.louiscouperus (2003).nl - Jacob Schorer. Tweeërlei maat: Kritische beschouwingen naar aanleiding van het nieuw voorgestelde artikel 248bis wetboek van strafrecht in het den 16 sept. 1910 gewijzigde wetsontwerp ter bestrijding tot bestrijding van zedeloosheid. The Hague 1911.

- Paul Snijders. "De Legenden van de Roze Lust:Het Haagse Zedenschandaal van 1920" at www

.louiscouperus (2003).nl - Adriaan Venema. Homosexualiteit in de Nederlandse literatuur Amsterdam/Brussel, Paris-Manteau (1972). ISBN 9022303063

- Jos Versteegen. "Nederlandse gay literatuur in de tweede helft van de jaren '90: Een overzicht" in Gay 2000 (1999)

- Hans Warren (editor). Herenliefde (1995) — a selection of homoerotic stories by Louis Couperus, Tom Lannoye, Maarten 't Hart, Gerrit Komrij, Eric de Kuyper, A. F. Th. van der Heijden and Bas Heijne.

- Werkgroep Liever Leven (Luc Versteylen et al.) De Paradijs Ervaring. Stil Leven Borgerhout (1981)

English-language sources

- Maaike Meijer (editor and introduction). The Defiant Muse: Dutch and Flemish Feminist Poems from the Middle Ages to the Present: A Bilingual Anthology. The Feminist Press at the City University of New York (1998)

- Catharine Smith. Apple Censors--Then Approves--Gay Kiss In Oscar Wilde Comic in Huffington Post, 25 November 2011.

- Saskia Wieringa. Female Desires: Same-Sex Relations and Transgender Practices Across Cultures. Columbia University Press (1999)