Hydraulic fracturing in Canada

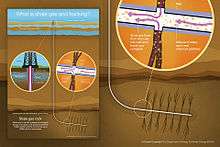

Schematic depiction of hydraulic fracturing for shale gas. | |

| Process type | Mechanical |

|---|---|

| Industrial sector(s) | Mining |

| Main technologies or sub-processes | Fluid pressure |

| Product(s) | Natural gas, petroleum |

| Inventor | Floyd Farris; J.B. Clark (Stanolind Oil and Gas Corporation) |

| Year of invention | 1947 |

| Hydraulic fracturing |

|---|

Shale gas drilling rig near Alvarado, Texas |

| By country |

| Environmental impact |

| Regulation |

| Technology |

| Politics |

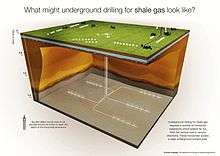

Hydraulic fracturing in Canada was first used in Alberta in 1953 to extract hydrocarbons from the giant Pembina oil field, the biggest conventional oil field in Alberta, which would have produced very little oil without fracturing. Since then, over 170,000 oil and gas wells have been fractured in Western Canada.[1][2]:1298 Hydraulic fracturing is a process that stimulates natural gas or oil in wellbores to flow more easily by subjecting hydrocarbon reservoirs to pressure through the injection of fluids or gas at depth causing the rock to crack or to widen existing cracks.[3]:4 New hydrocarbon production areas have been opened as hydraulic fracturing stimulating techniques are coupled with more recent advances in horizontal drilling. Complex wells that are many hundreds or thousands of metres below ground are extended even further through drilling of horizontal or directional sections.[4] Massive fracturing has been widely used in Alberta since the late 1970s to recover gas from low-permeability sandstones such as the Spirit River Formation.[5]:1044 The productivity of wells in the Cardium, Duvernay, and Viking formations in Alberta, Bakken formation in Saskatchewan, Montney and Horn River formations in British Columbia would not be possible without hydraulic fracturing technology. Hydraulic fracturing has revitalized legacy oilfields.[6] "Hydraulic fracturing of horizontal wells in unconventional shale, silt and tight sand reservoirs unlocks gas, oil and liquids production that until recently was not considered possible."[7] Conventional oil production in Canada was on a decrease since about 2004 but this changed with the increased production from these formations using hydraulic fracturing.[6] Hydraulic fracturing is one of the primary technologies employed to extract shale gas or tight gas from unconventional reservoirs.[3]

In 2012 Canada averaged 356 active drilling rigs, coming in second to the United States with 1,919 active drilling rigs. The United States represents just below 60 percent of worldwide activity.[8]:21

Geological formations

The Spirit River, Cardium, Duvernay, Viking, Montney (AB and BC), and Horn River formations are stratigraphical units of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) which underlies 1,400,000 square kilometres (540,000 sq mi) of Western Canada and which contains one of the world's largest reserves of petroleum and natural gas. The Bakken formation is a rock unit of the Williston Basin that extends into southern Saskatchewan. In the early 2000s significant increases in production the Williston Basin began because of application of horizontal drilling techniques, especially in the Bakken Formation.[9]

- Outline of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin

North America showing position of Williston Basin

North America showing position of Williston Basin Location of Williston Basin (USGS)

Location of Williston Basin (USGS)

Technologies

The first commercial application of hydraulic fracturing was by Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company (Howco) in 1949 in Stephens County, Oklahoma and in Archer County, Texas, using a blend of crude oil and a proppant of screened river sand into existing wells with no horizontal drilling.[3]:5[10]:27 In the 1950s about 750 US gal (2,800 l; 620 imp gal) of fluid and 400 lb (180 kg) were used. By 2010 treatments averaged "approximately 60,000 US gal (230,000 l; 50,000 imp gal) of fluid and 100,000 lb (45,000 kg) of propping agent, with the largest treatments exceeding 1,000,000 US gal (3,800,000 l; 830,000 imp gal) of fluid and 5,000,000 lb (2,300,000 kg) of proppant."[10]:8[11]

In 2011 the Wall Street Journal summarized the history of hydraulic fracturing,[4]

"Only a decade ago Texas oil engineers hit upon the idea of combining two established technologies to release natural gas trapped in shale formations. Horizontal drilling—in which wells turn sideways after a certain depth—opens up big new production areas. Producers then use a 60-year-old technique called hydraulic fracturing—in which water, sand and chemicals are injected into the well at high pressure—to loosen the shale and release gas (and increasingly, oil)."— Wall Street Journal 2011

Horizontal oil or gas wells were unusual until the 1980s. Then in the late 1980s, operators along the Texas Gulf Coast began completing thousands of oil wells by drilling horizontally in the Austin Chalk, and giving 'massive' hydraulic fracturing treatments to the wellbores. Horizontal wells proved much more effective than vertical wells in producing oil from the tight chalk.[11]

Cost and lifespan of hydraulic fracturing

Oil producers spend US$12 million upfront to drill a well but it is so efficient and produces so well during its short, 18-month lifespan, that oil producers using this technology can still make a profit even with oil at $50 a barrel.[12]

Alberta

Because of its vast oil and gas resources, Alberta is the busiest province in terms of hydraulic fracturing. The first well to be fractured in Canada was the discovery well of the giant Pembina oil field in 1953 and since then over 170,000 wells have been fractured. The Pembina field is a "sweet spot" in the much larger Cardium Formation, and the formation is still growing in importance as multistage horizontal fracturing is increasingly used.

The Alberta Geological Survey evaluated the potential of new fracturing techniques to produce oil and gas from shale formations in the province, and found at least five prospects which show immediate promise: the Duvernay Formation, the Muskwa Formation, the Montney Formation, the Nordegg Member, and the basal Banff and Exshaw Formations.[13] These formations may contain up to 1.3 quadrillion cubic feet (37×1012 m3) of gas-in-place. Since shale resources are in the early stages of development in Alberta, it is not known what portion of these resources can be economically produced.

Even as the price of oil declined dramatically in 2014, hydraulic fracturing in so-called "sweet spots" such as the Cardium and Duvernay in Alberta, remained financially viable.[14]

British Columbia

Talisman Energy, which was recently acquired by the Spanish company Repsol, "has extensive operations in the Montney shale gas area."[15] In late July 2011 the Government of British Columbia gave Talisman Energy, whose head office is in Calgary, a twenty-year long-term water licence to draw water from the BC Hydro-owned Williston Lake reservoir.

In 2013, the Fort Nelson First Nation, a remote community in northeastern B.C. with 800 community members, expressed frustration with royalties associated with gas produced through hydraulic fracturing in their territory. Three of British Columbia's four shale-gas reserves – the Horn River, Liard and Cordova Basins are on their lands. Those basins hold the key to B.C.’s LNG ambitions." [16]

Saskatchewan

The Bakken shale oil and gas boom underway since 2009, driven by hydraulic fracturing technologies, has contributed to record growth, high employment rates and increase in population, in the province of Saskatchewan. Hydraulic fracturing has benefited small towns like Kindersley which saw its population increase to over 5,000 with the boom. Kindersley sells its treated municipal wastewater to oilfield service companies to use in hydraulic fracturing.[6] As the price of oil dropped dramatically in late 2014 partially in response to the shale oil boom, towns like Kinderslely are more vulnerable.

Quebec

The Utica Shale, a stratigraphical unit of Middle Ordovician age underlies much of the northeastern United States and in the subsurface in the provinces of Quebec and Ontario.[18]

Drilling and producing from the Utica Shale began in 2006 in Quebec, focusing on an area south of the St. Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City. Interest has grown in the region since Denver-based Forest Oil Corp. announced a significant discovery there after testing two vertical wells. Forest Oil said its Quebec assets may hold as much as four trillion cubic feet of gas reserves,[19] and that the Utica shale has similar rock properties to the Barnett shale in Texas.

Forest Oil, which has several junior partners in the region, has drilled both vertical and horizontal wells. Calgary-based Talisman Energy has drilled five vertical Utica wells, and began drilling two horizontal Utica wells in late 2009 with its partner Questerre Energy, which holds under lease more than 1 million gross acres of land in the region. Other companies in the play are Quebec-based Gastem and Calgary-based Canbriam Energy.

The Utica Shale in Quebec potentially holds 4×1012 cu ft (110×109 m3) at production rates of 1×106 cu ft (28,000 m3) per day[19][20] From 2006 through 2009 24 wells, both vertical and horizontal, were drilled to test the Utica. Positive gas flow test results were reported, although none of the wells were producing at the end of 2009.[21] Gastem, one of the Utica shale producers, took its Utica Shale expertise to drill across the border in New York state.[22]

In June 2011, the Quebec firm Pétrolia claimed to have discovered about 30 billion barrels of oil on the island of Anticosti, which is the first time that significant reserves have been found in the province.[23]

Debates on the merits of hydraulic fracturing have been on-going in Quebec since at least 2008.[24][25] In 2012 the Parti Québécois government imposed a five-year moratorium on hydraulic fracturing in the region between Montreal and Quebec City, called the St. Lawrence Lowlands, with a population of about 2 million people.[25]

Prior to announcing her provincial election campaign, former Premier of Quebec and former leader of the Parti Québécois (PQ), Pauline Marois, announced that the PQ party would spend $115 million to help finance two exploratory shale gas operations as a prelude to hydraulic fracturing for oil on Anticosti Island that would have been a catalyst for ending the moratorium.[26]|:37[25][27]

In February 2014, prior to announcing her provincial election campaign, former Premier of Quebec and former leader of the Parti Québécois (PQ), Pauline Marois, announced that the provincial government would help finance two exploratory shale gas operations as a prelude to hydraulic fracturing on the island, with the province pledging $115-million to finance drilling for two separate joint ventures in exchange for rights to 50% of the licences and 60% of any commercial profit.[25][26]:37[28] It was the first oil and gas deal of any size for the province. With the change in government that occurred in April 2014, the Liberals of Philippe Couillard could change that decision.

Petrolia Inc., Corridor Resources and Maurel & Prom formed one joint-venture, while Junex Inc. was still seeking a private partner.[29]

In November 2014 a report published by Quebec’s advisory office of environmental hearings, the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement (BAPE), found "shale gas development in the Montreal-to-Quebec City region wouldn’t be worthwhile." BAPE warned of a "magnitude of potential impacts associated with shale gas industry in an area as populous and sensitive as the St. Lawrence Lowlands."[24][30] The Quebec Oil and Gas Association challenged the accuracy of BAPE's report. On 16 December 2014 Quebec's Premier Philippe Couillard responded to the BAPE report stating there will be no hydraulic fracturing due to a lack of economic or financial interest and a lack of social acceptability.[25]

Gallery

Scale diagram of a shale gas well showing large separation between aquifer and shale source rock

Scale diagram of a shale gas well showing large separation between aquifer and shale source rock Scale diagram showing how many wells can drain gas from a large area from a single pad

Scale diagram showing how many wells can drain gas from a large area from a single pad.jpg) A well from drilling to abandonment

A well from drilling to abandonment

Hydraulic fracturing fluid

Under the Canada Oil and Gas Operations Act, the National Energy Board (NEB) requests operators to submit the composition of the hydraulic fracturing fluids used in their operation that will be published online for public disclosure on the FracFocus.ca website.[31]

Possible related earthquakes

| Time (local) | M | Epicenter | Comments | Coordinates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 14, 2015 09:06:25 | 3.8 | 38 km (24 mi) west of Fox Creek, AB | No damage reported | 54°21′00″N 117°22′48″W / 54.35000°N 117.38000°W | [32][33] |

| January 22, 2015 23:49:18 | 4.4 | 36 km (22 mi) west of Fox Creek, AB | Lightly felt in Fox Creek | 54°28′12″N 117°15′36″W / 54.47000°N 117.26000°W | [32][33] |

| June 13, 2015 17:57:55 | 4.6 | 36 km (22 mi) east of Fox Creek, AB | Felt lightly in Drayton Valley, Edmonton and Edson | 54°06′07″N 116°57′00″W / 54.10194°N 116.95000°W | [33][34][35] |

| January 12, 2016 12:27:21 | 4.4 | 25 km (16 mi) north of Fox Creek, AB | Felt as far south as St. Albert, just northwest of Edmonton. | 54°28′12″N 117°15′36″W / 54.47000°N 117.26000°W | [36][37][38] |

See also

- Shale gas by country

- List of countries by recoverable shale gas

- Directional drilling

- Environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing

- Environmental impact of petroleum

- Environmental impact of the oil shale industry

- ExxonMobil Electrofrac

Citations

- ↑ Stephen Ewing (November 25, 2014). "Five facts on fracking". Calgary Herald. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Milne, J.E.S.; Howie, R.D. (June 1966), "Developments in eastern Canada in 1965", Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 50 (6)

- 1 2 3 "Understanding Hydraulic Fracturing" (PDF), Canadian Society for Unconventional Gas (CSUG), 2011, retrieved 9 January 2015

- 1 2 The Facts About Fracking, 25 June 2011, retrieved 9 January 2015

- ↑ Cant, Douglas J.; Ethier, Valerie G. (August 1984), "Lithology-dependent diagenetic control of reservoir properties of conglomerates, Falher member, Elmworth Field, Alberta,", Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists, 68 (8)

- 1 2 3 Ewart, Stephen (25 November 2014). "Small producers, towns could feel pinch as fracking boom puts pressure on oil prices". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ "Technologies and the Geology Perspective", Chinook Consulting Services, Calgary, Alberta, 2004, retrieved 9 January 2015

- ↑ Maugeri, Leonardo (June 2013), The Shale Oil Boom: a U. S. Phenomenon (PDF), The Geopolitics of Energy Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School, retrieved 2 January 2014

- ↑ Pitman, Janet K.; Price, Leigh C.; LeFever, Julie A. (2001), Diagenesis and Fracture Development in the Bakken Formation, Williston Basin: Implications for Reservoir Quality in the Middle Member, U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper (1653)

- 1 2 Montgomery, Carl T.; Smith, Michael B. (December 2010), "Hydraulic fracturing: history of an enduring technology" (PDF), JPT

- 1 2 Bell, C.E; et al. (1993), Effective diverting in horizontal wells in the Austin Chalk, archived from the original on 2013-10-05, retrieved 2016-05-14

- ↑ Why Cheap Oil Doesn't Stop the Drilling, 5 March 2015, retrieved 6 March 2015

- ↑ Rokosh, C.D.; et al. (June 2012). "Summary of Alberta's Shale- and Siltstone-Hosted Hydrocarbon Resource Potential". Alberta Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2015-05-20. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ McCarthy, Shawn; Lewis, Jeff (2 December 2014), "The shale slowdown: Oil's price plunge hits U.S. production", The Globe and Mail, Ottawa and Calgary

- ↑ Stueck, Wendy (30 October 2013), "Leak shuts fracking-water storage pond; Talisman says environmental risks are low", The Globe and Mail, Vancouver

- ↑ Hunter, Justine (29 October 2013), "B.C. First Nation calls for natural-gas royalties amid frustration over fracking", The Globe and Mail, Victoria, BC

- ↑ State of North Dakota Bakken Formation Reserve Estimates (PDF).

- ↑ Lexicon of Canadian Geologic Units. "Utica Shale". Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- 1 2 "Press Releases and Notices", Forest Oil Corporation, retrieved 2016-05-14

- ↑ "Press release Investors", Junex, 2008, archived from the original on 2012-03-02, retrieved 2016-05-14

- ↑ Eaton, Susan R. (January 2010), "Shale play extends to Canada", AAPG Explorer, pp. 10–24

- ↑ "New York to get Utica shale exploration". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. 106 (12): 41. 24 March 2008. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ↑ Proulx, André (June 2011). "Petrolia: First Resource Assessment of Macasty Shale, Anticosti Island, Quebec". Marketwire. Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- 1 2 McCarthy, Shawn (15 December 2014), "Fracking dealt another setback by Quebec report", The Globe and Mail, Ottawa, retrieved 2 January 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vendeville, Geoffrey (16 December 2014), "Couillard rules out fracking", Montreal Gazette, Montreal, retrieved 2 January 2015

- 1 2 Smith, Karan; Rosano, Michela, "Quebec Utica shale gas", Canadian Geographic, Energy Rich, pp. 34–40

- ↑ Quebec installs outright moratorium on hydraulic fracturing, International Business Times, 4 April 2012.

- ↑ "Quebec installs outright moratorium on hydraulic fracturing", International Business Times, 4 April 2012

- ↑ Quebec oil juniors hopeful new Liberal government will honour Anticosti deals, 8 April 2014

- ↑ "Les enjeux liés à l'exploration et l'exploitation du gaz de schiste dans le shale d'Utica des basses-terres du Saint-Laurent" (PDF), BAPE, November 2014, retrieved 2 January 2014

- ↑ NEB 2014.

- 1 2 Howell, David (31 January 2015). "Fracking possible cause of 4.4-magnitude Fox Creek earthquake". Edmonton Journal. Postmedia Network. Archived from the original on 2015-02-08. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Search the Earthquake Database". Natural Resources Canada. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Paige Parsons (June 13, 2015). "Multiple earthquakes detected this year near Fox Creek". Edmonton Journal. Postmedia Network. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

- ↑ "M4.6 - 34km SSW of Fox Creek, Canada". USGS. USGS. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ "M4.6 - 34km SSW of Fox Creek, Canada". USGS. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ "Earthquake Details (2016-01-12)". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- ↑ "St. Albert feels tremors from earthquake near Fox Creek By Emily Mertz an". Corus Entertainment Inc. Global News. 12 January 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

References

- "National Energy Board Procedures for the Public Disclosure of Hydraulic Fracturing Fluid Composition Information", NEB, 1 October 2014, retrieved 3 December 2014

External links

- "Shale Gas", Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, 2015, retrieved 2 January 2015

- "Understanding Hydraulic Fracturing" (PDF), Canadian Society for Unconventional Gas, Calgary, Alberta, nd, retrieved 2 January 2014

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hydraulic fracturing in Canada. |

| Wikinews has related news: Disposal of fracking wastewater poses potential environmental problems |

| Look up hydraulic fracturing in canada in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |