Henry Villard

| Henry Villard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Ferdinand Heinrich Gustav Hilgard April 10, 1835 Speyer, Rhenish Bavaria |

| Died |

November 12, 1900 (aged 65) Dobbs Ferry, New York |

| Signature | |

|

| |

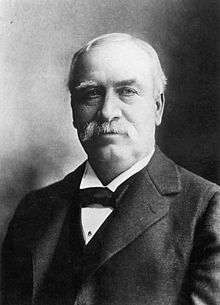

Henry Villard (April 10, 1835 – November 12, 1900) was an American journalist and financier who was an early president of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Born and raised Ferdinand Heinrich Gustav Hilgard in the Rhenish Palatinate of the Kingdom of Bavaria, Villard clashed with his more conservative father over politics, and was sent to a semi-military academy in northeastern France. As a teenager, he emigrated to the United States without his parents' knowledge. He changed his name to avoid being sent back to Europe, and began making his way west, briefly studying law as he developed a career in journalism. He supported John C. Frémont of the newly established Republican Party in his presidential campaign in 1856, and later followed Abraham Lincoln's 1860 campaign.

Villard became a war correspondent, first covering the American Civil War, and later being sent by the Chicago Tribune to cover the Austro-Prussian War. He became a pacifist as a result of his experiences covering the Civil War. In the late 1860s he married women's suffrage advocate Helen Frances Garrison, and returned to the U.S., only to go back to Germany for his health in 1870.

While in Germany, Villard became involved in investments in American railroads, and returned to the U.S. in 1874 to oversee German investments in the Oregon and California Railroad. He visited Oregon that summer, and being impressed with the region's natural resources, began acquiring various transportation interests in the region. During the ensuing decade he acquired several rail and steamship companies, and pursued a rail line from Portland to the Pacific Ocean; he was successful, but the line cost more than anticipated, causing financial turmoil. Villard returned to Europe, helping German investors acquire stakes in the transportation network, and returned to New York in 1886.

Also in the 1880s, Villard acquired the New York Evening Post and The Nation, and established the predecessor of General Electric. He was the first benefactor of the University of Oregon, and contributed to other universities, churches, hospitals, and orphanages. He died of a stroke at his country home in New York in 1900.

Early life and education

He was born in Speyer, Palatinate, Kingdom of Bavaria. His parents moved to Zweibrücken in 1839, and in 1856 his father, Gustav Leonhard Hilgard (who died in 1867), became a justice of the Supreme Court of Bavaria, at Munich. He belonged to the Reformed Church. His mother, Katharina Antonia Elisabeth (Lisette) Pfeiffer, was Catholic. While he had aristocratic tendencies, he shared the republican interests of much of the Hilgard clan. His granduncle Theodore Erasmus Hilgard had emigrated to the United States during a clan move of 1833-1835 to Belleville, Illinois; the granduncle had resigned a judgeship so his children could be raised as "freemen." Villard was also a distant relative of the physician and botanist George Engelmann who resided in St. Louis, Missouri.[1]

Villard entered a Gymnasium (equivalent of a United States high school) in Zweibrücken in 1848, which he had to leave because he sympathized with the revolutions of 1848 in Germany. He had broken up a class by refusing to mention the King of Bavaria in a prayer, justifying his omission by citing his loyalty to the provisional government. Another time, after watching a session of the Frankfurt Parliament, he came home in a Hecker hat with a red feather in it. Two of his uncles were strongly in sympathy with the revolution, but his father was a conservative, and disciplined him by sending the boy to continue his education at the French semi-military academy in Phalsbourg (1849–50).[2] Originally his punishment was to be apprenticed, but his father compromised on the military school.[1] Villard showed up a for classes a month early so he could be tutored in the French language beforehand by the novelist Alexandre Chatrian.[1][3] He later attended the Gymnasium of Speyer in 1850-52, and the universities of Munich and Würzburg in 1852-53. In Munich he was a member of the student fraternity Corps Franconia. In 1853, having had a disagreement with his father, he emigrated—without his parents' knowledge—to the United States.

Journalism

On emigrating to America, he adopted the name Villard, the surname of a French schoolmate at Phalsbourg, to conceal his identity from anyone intent on making him return to Germany.[2][3] Making his way westward in 1854, he lived in turn at Cincinnati; Belleville, Illinois and Peoria, Illinois where he studied law for a time;[4] and Chicago where he wrote for newspapers. Along with newspaper reporting and various jobs, in 1856 he attempted unsuccessfully to establish a colony of "free soil" Germans in Kansas. In 1856-57 he was editor, and for part of the time was proprietor of the Racine Volksblatt, in which he advocated the election of presidential candidate John C. Frémont of the newly founded Republican Party.

Thereafter he was associated with the New Yorker Staats-Zeitung, for whom he covered the Lincoln-Douglas debates;[2] Frank Leslie's; the New York Tribune; and with the Cincinnati Commercial Gazette. In 1859, as correspondent of the Commercial, he visited the newly discovered gold region of Colorado. On his return in 1860, he published The Pike's Peak Gold Regions. He also sent statistics to the New York Herald that were intended to influence the location of a Pacific railroad route.[4] He followed Lincoln throughout the 1860 presidential campaign, and was on the presidential train to Washington in 1861.[2] He was correspondent of the New York Herald in 1861.

During the Civil War, he was correspondent for the New York Tribune (with the Army of the Potomac, 1862–63) and was at the front as the representative of a news agency established by him in that year at Washington (1864). Out of his experiences reporting the Civil War, he became a confirmed pacifist.[2] In 1865, when Horace White became managing editor of the Chicago Tribune, Villard became its Washington correspondent.[3] In 1866, he was the correspondent of that paper in the Prusso-Austrian War. He stayed on in Europe in 1867 to report on the Paris Exposition.

At the close of the Civil War, he married Helen Frances Garrison, the daughter of the anti-slavery campaigner William Lloyd Garrison, on January 3, 1866. He returned to the United States from his correspondent duties in Europe in June 1868, and shortly afterward was elected secretary of the American Social Science Association, to which he devoted his labors until 1870, when he went to Germany for his health.[4]

Transportation

In Germany, while living at Wiesbaden, he engaged in the negotiation of American railroad securities. After the Panic of 1873, when many railroad companies defaulted in the payment of interest, he joined several committees of German bond holders, doing the major part of the committee work, and in April 1874 he returned to the United States to represent his constituents, and especially to execute an arrangement with the Oregon and California Railroad Company.[4]

Villard first visited Portland, Oregon in July 1874.[5] On visiting Oregon, he was impressed with the natural wealth of the region, and conceived the plan of gaining control of its few transportation routes. His clients, who were also large creditors also of the Oregon Steamship Company, approved his scheme, and in 1875 Villard became president of both the steamship company and the Oregon and California Railroad. In 1876, he was appointed a receiver of the Kansas Pacific Railroad as the representative of European creditors. He was removed in 1878, but continued the contest he had begun with Jay Gould and finally obtained better terms for the bond holders than they had agreed to accept.[4]

The Pacific Northwest was the booming sector of American expansion. European investors in the Oregon and San Francisco Steamship Line, after building new vessels, became discouraged, and in 1879 Villard formed an American syndicate and purchased the property. He also acquired that of the Oregon Steam Navigation Company, which operated fleets of steamers and portage railroads on the Columbia River. The three companies that he controlled were amalgamated under the name of the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company.[4]

He began the construction of a railroad up Columbia River. On failing in his effort to obtain a permanent agreement with the Northern Pacific Railway, which had begun its extension into the Washington Territory, Villard used his Columbia River steamship line as his railroad's outlet to the Pacific Ocean. He then succeeded in obtaining a controlling interest in the Northern Pacific property, and organized a new corporation that was named the Oregon and Transcontinental Company. This acquisition was achieved with the aid of a syndicate, called by the press a “blind pool,” composed of friends who had loaned him $20 million without knowing his intentions.[3][6] After some contention with the old managers of the Northern Pacific road, Villard was elected president of a reorganized board of directors on 15 September 1881.[4]

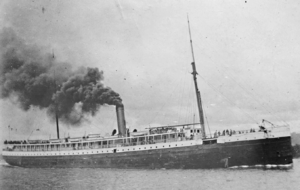

After attending Thomas Edison's 1879 Menlo Park, New Jersey New Year's Eve demonstration of his incandescent light bulb, Villard requested that Edison install one of his lighting systems onboard Oregon Railroad and Navigation's new steamship, the Columbia. Although hesitant at first, Edison eventually agreed to Villard's request. After being mostly completed at the John Roach & Sons shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania, the Columbia was sent to New York City, where Edison and his personnel installed its lighting system. This made Columbia the first commercial application of Edison's light bulb. Columbia would later sink on 20 July 1907 following a collision with the steam schooner San Pedro off Shelter Cove, California killing 88 people.[7][8][9][10]

With the aid of the Oregon and Transcontinental Company, his railroad line to the Pacific Ocean was completed, but at the time when it was opened to traffic with festivities, in September 1883. The project had cost more than expected, and some months later these companies experienced a financial collapse. Villard's financial embarrassment caused the collapse of the stock exchange firm of Decker, Howell, & Co., and Villard's attorney, William Nelson Cromwell, used $1,000,000 to promptly settle with creditors.[3] On 4 January 1884, Villard resigned the presidency of the Northern Pacific. After spending the intervening time in Europe, he returned to New York City in 1886, and purchased for German capitalists large amounts of the securities of the transportation system that he was instrumental in creating, becoming again director of the Northern Pacific, and on 21 June 1888, again president of the Oregon and Transcontinental Company.[3][4]

More acquisitions and mergers

In 1881, he acquired the New York Evening Post and The Nation. These publications were then edited by his friend Horace White in conjunction with Edwin L. Godkin and Carl Schurz. This marked White's re-entry into journalism. He also helped manage Villard's railroad and steamship interests 1876-1891. They had met as newspaper reporters during the Civil War.[11]

Villard had also had a hand in the large electric power business founded by Thomas Edison, merging the Edison Electric Light Company, Edison Lamp Company of Newark, New Jersey and the Edison Machine Works at Schenectady, New York to form the Edison General Electric Company. Villard was the president of this concern until 1892 when he was forced out after financier J. P. Morgan engineered a merger with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company that put that company's board in control of the new enterprise, renamed General Electric.[12]

Philanthropy

In 1883 he paid the debt of the University of Oregon, and gave the institution $50,000. As the University of Oregon's first benefactor, he had Villard Hall, the second building on campus, named after him.[13] He liberally aided the University of Washington Territory.[4] He also aided Harvard University, Columbia University, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History.[3]

In Speyer he was a main benefactor for the construction of the Memorial Church and a new hospital. There he is still known as Heinrich Hilgard, and a street is named after him (Hilgardstrasse). He has been honoured with the freedom of the city, and there is a bust of him on the compound of the Speyer Diakonissen Hospital.

In Zweibrücken he built an orphanage in 1891. He has also financed a school for nurses. He devoted large sums to the Industrial Art School of Rhenish Bavaria, and to the foundation of fifteen scholarships for the youth of that province.[4]

He supported Bandelier in his research on South American history and archaeology.[3]

Death

Henry Villard died of a stroke at his country home, Thorwood Park, in Dobbs Ferry, New York. He was interred in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York. His autobiography was published posthumously, in 1904.[14] The monument at his grave site was executed by Karl Bitter.[15]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Memoirs of Henry Villard. 1. Boston: Houghton and Mifflin Co. 1904.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carl Wittke (1952). Refugees of Revolution: The German Forty-Eighters in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 336–337.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Henry Villard Is Dead—Capitalist and promoter expires at his country home" (PDF). New York Times. November 13, 1900. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Villard, Henry". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Wilson, James Grant; Fiske, John, eds. (1900). "Villard, Henry". Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton. - ↑ MacColl, E. Kimbark (November 1976). The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon 1885 to 1915. Portland, Oregon: The Georgian Press Company. OCLC 2645815.

- ↑ John Huibregtse (1999). "Villard, Henry". American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Jehl, Francis Menlo Park reminiscences : written in Edison's restored Menlo Park laboratory, Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, Whitefish, Mass, Kessinger Publishing, 1 July 2002, page 564

- ↑ Dalton, Anthony A long, dangerous coastline : shipwreck tales from Alaska to California Heritage House Publishing Company, 1 Feb 2011 - 128 pages

- ↑ Swann, p. 242.

- ↑ "Lighting A Revolution: 19th Century Promotion". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Logsden (1999). "White, Horace". American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Robert L. Bradley, Jr., Edison to Enron: Energy Markets and Political Strategies, John Wiley & Sons - 2011, pages 28-29

- ↑ University of Oregon (2004). "Villard Hall". Oregon Photo Tour. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ↑ "Memoirs of Henry Villard, Journalist and Financier, 1835-1900," (1904, Houghton Mifflin Co.)(two volumes).

- ↑ Karl Bitter: Architectural Sculptor 1867-1915, University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, 1967 pp. 94-96.

References

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Villard, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Villard, Henry". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. -

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Villard, Henry". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Gilman, D. C.; Thurston, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Villard, Henry". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

Further reading

- Buss, Dietrich G. Henry Villard: a study of transatlantic investments and interests, 1870-1895 (Arno Press, 1978).

- Cochran, Thomas C. (1949) "The Legend of the Robber Barons." Explorations in Economic History 1#5 (1949) online deals largely with Villard.

- Alexandra Villard de Borchgrave; John Cullen (2001). Villard: The Life and Times of an American Titan. New York: Doubleday.

- Kobrak, Christopher. "A Reputation for Cross-Cultural Business: Henry Villard and German Investment in the United States ." In Immigrant Entrepreneurship: German-American Business Biographies, 1720 to the Present, vol. 2, edited by William J. Hausman. German Historical Institute. Last modified September 30, 2015.

Primary sources

- Memoirs of Henry Villard (2 vols., Boston, 1904)

- The Early History of Transportation in Oregon Edited by Oswald Garrison Villard (University of Oregon Press, 1944) Reviewed here

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henry Villard. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Henry Villard |

- Brief biography of Henry Villard

- Helmut Schwab, "Henry Villard": a more detailed biography

- Henry Villard Business Papers at Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

| Preceded by Frederick H. Billings |

President of Northern Pacific Railway 1881–1884 |

Succeeded by Robert Harris |